A New Proposal for Overcoming Racism and Renewing the Promise of America

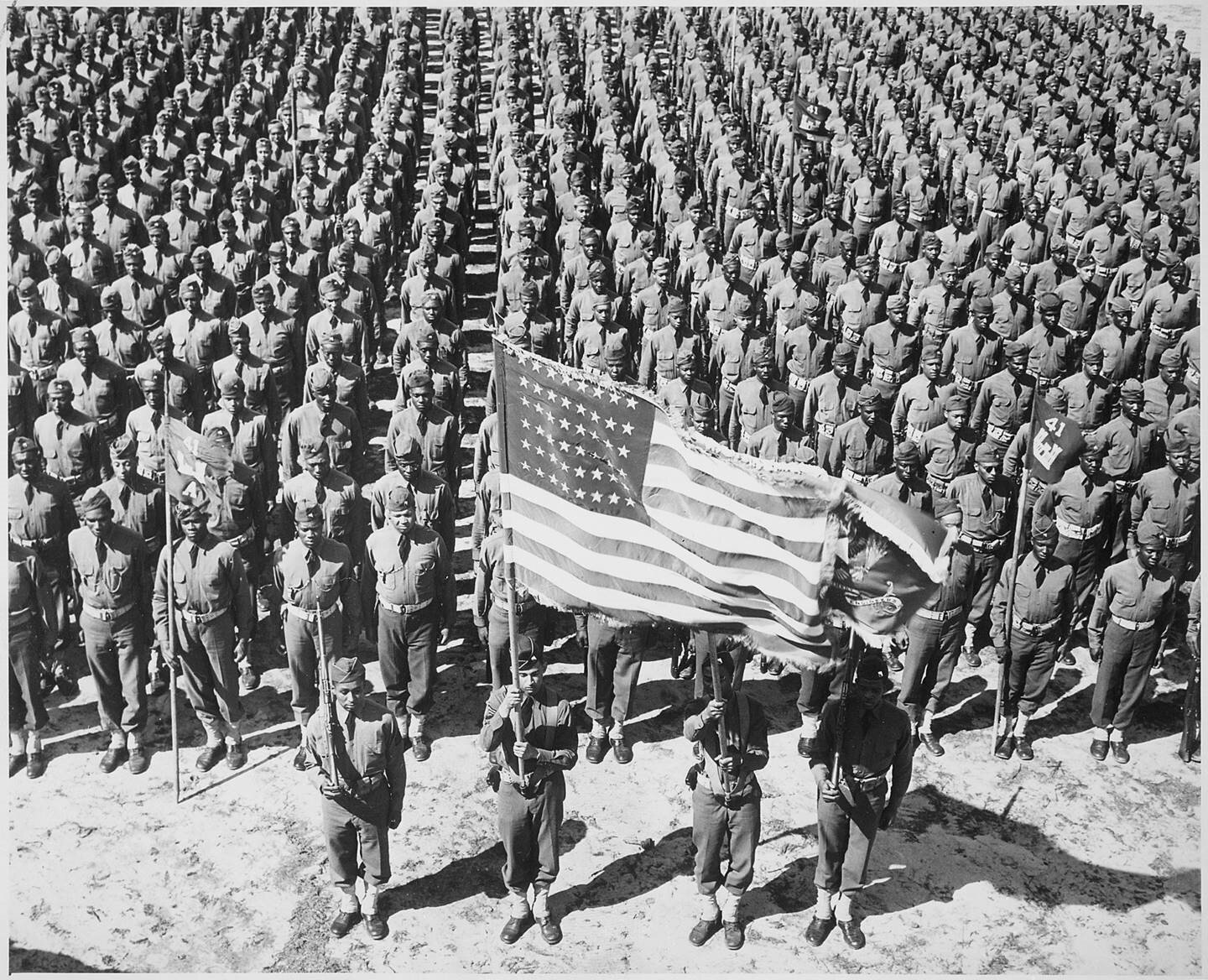

Source: National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The debate over what it would take for the United States to reckon with and transcend the scourge of racism is about to be enriched by Theodore R. Johnson with his new book, When the Stars Begin to Fall: Overcoming Racism and Renewing the Promise of America. Ted Johnson brings a unique and illuminating vantage point to this debate. A retired U.S. Navy Commander, he taught at the Naval War College, was a White House Fellow in the Obama Administration, and wrote speeches for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of staff, among his other assignments ashore and at sea during his 20 years in the service. Ted then went on to do a doctorate in law and policy and has emerged as a leading expert on the political beliefs and behavior of Black Americans. He writes regularly on these topics for the New York Times Magazine and the Washington Post, among other publications. He also directs the Fellows Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Alongside his military, academic, and journalistic accomplishments, what makes Ted's work on racism and the politics of Black Americans so powerful is how he weaves in the intensely personal experiences of racism he and his forbears have endured. He does so with great effect, for example, in an essay he wrote for the National Review after George Floyd's murder, "America Begins to See More Clearly Now What Its Black Citizens Always Knew." The title of that post aptly captures the impact Ted is having on so many of his readers, myself included. I recently caught up with Ted to preview some of the core themes of his book. (It will be published on June 8, and you can pre-order it here). What follows is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

DS: What prompted you to write When the Stars Begin to Fall?

TJ: I had all these life experiences that felt like puzzle pieces, and I tried to piece them together in a way that would tell a bigger story about race in America. The book really started as my dissertation. I wanted to write the definitive book on modern black voting behavior to explain why it is that 90 percent of black Americans vote for Democratic congressional and presidential candidates, yet their political views span the political spectrum. Then in November of 2016, Donald Trump wins the presidential election, and it's all about the white working-class, Hillbilly Elegy, and diners in communities where the mills are gone. No one was interested in my book topic. The advice I got from one agent was if you want to talk about Black America, talk more broadly about race and use the Black American experience as a vehicle for a bigger conversation -- beyond politics, beyond the economy. Talk about America's first principles and whether we're living up to them. That's when I started to pull together bits and pieces from my personal narrative and my family's history to answer the question about the major issue troubling the nation and why we have not managed to live up to our professed principles.

DS: It's always dangerous to ask someone to summarize their dissertation, but could you explain why, despite the range of political views in the African American Community, there is this pattern of highly concentrated allegiance to one party?

TJ: Black voting behavior is a reaction to racism and racial hierarchy in the United States. It has been since the freedmen first got the opportunity to vote. Black voters have always clustered themselves in the party that doesn't welcome white segregationists. That is the whole story of black voting throughout our history. It's been so pervasive and so enduring, from the end of slavery, the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, and Reconstruction through the Great Migration, the realignment during the Civil Rights era, and the first black president. Through it all, black voters have almost always voted 90 percent or so for the party that stood in opposition to white segregationists and to white Americans with high levels of racial resentment.

DS: You describe racism as an existential threat to the United States. Say more about that.

TJ: While the United States, the geopolitical entity, has proven it can live quite comfortably with racism coursing through the nation, the idea of America cannot. This idea is the embodiment of the principles, ideals, and values that the nation was founded on. The United States of America was founded in the hope of becoming a more perfect union. My argument is that racism is an existential threat to the idea of equality, liberty, prosperity, and opportunity that the term America has come to symbolize. Racism and America's principles cannot coexist and survive. One has to give way to the other when both are present. Now we can be a work in progress. So as long as we're making inroads against structural racism, then we are moving closer to what America symbolizes, but when we stop making progress or we reverse our course, then America – the idea of America, the promise of America – is in danger.

DS: You argue that the best way forward is for us to see racism not so much as a failing of individuals or groups, but as a crime of the state. Why is this reframing important?

TJ: This is one of the biggest challenges in talking about racism today. We start to play the blame game as soon as the word racism comes up. The bickering that occurs when we try to identify those who are harmed and those who are responsible for the harm usually turns black people or people of color against white people. That is a group-versus-group issue that is not at all constructive in resolving the range of racial inequalities that exist in the country. It serves to divide us along lines of color and creates a weakness that those with power can exploit. It does nothing to build bonds of connection between the citizenry. What I want to do is show that everyone is harmed when racism is present in our society.

There are some people who harbor racial hatred for black people in their hearts, but I believe they are such a minority in our society. The vast majority of the nation recognizes that it's not cool to hate someone just because of the group they belong to. But they don't accept that society has been structured in a way that advantages some over others. This presupposes that if you are in the group that has been advantaged by our current structure, whatever it is you have, you didn't really work for that. You didn't earn it. People impute all these meanings to the word racism based on how society talks about the issue that serves to divide us and then doesn't allow us to find common ground.

So, I think reframing it as a crime of the state shows what we're really talking about here. We have a set of laws and regulations and policies that perpetuate outcomes that disadvantage some groups over others, and that by definition are racist. Not because they intentionally do it, but because some groups are just disadvantaged for historical reasons that are coded into our structures. Everyone is being harmed by racism because it divides the public and allows those with power to hold on to it. And if our policies and laws are perpetuating this sort of racism - structural racism - then the way to defeat it is to hold the state accountable to take actions necessary to reverse the thing that they're allowing to persist. That is not just a job for those groups that are disadvantaged by structural racism. We're all harmed by its presence. It prevents the nation from living up to its principles, which ostensibly is a concern for everyone, no matter their race or ethnicity. Defining racism in this way allows for common ground, for people to come together across the color line and hold the state responsible for rigging outcomes.

DS: You are skeptical that the sort of civil rights legislation and policies we have turned to in the past will address our current challenges on racial equity. Why is that? What do we need for progress now?

TJ: As long as a group of people is valued less in society than another group, it doesn't matter what laws or policies you implement or enact. As Princeton professor Eddie Glaude, Jr. has argued, this value gap is going to ensure inequality is the end product. The implementation of policies and statutes gets distorted when everyone doesn't recognize that the rights and privileges of citizenship extend to everyone. Most of the times that we've seen transformational statutes or Supreme Court holdings on civil rights or race relations, it's in a catastrophe like the Civil War, or the Cold War with the Soviet Russia. That was why so much racial progress happened between the desegregation of the military in 1948 and the Fair Housing Act in 1968. Civil rights usually piggybacks on the national interest, and that has been when change happens. But we don't close the value gap. We are acting out of political expediency, not out of a recognition of another group's inherent value and inclusion in the American project.

At the end of the book, I make five recommendations, and only one of them is about laws. We need democracy reform -- voting rights protections, getting the dark money out of politics, addressing gerrymandering – a lot of the things that are now in HR1. But the other four recommendations have nothing to do with statutes that protect the process or system of democracy. They are about how we can become better actors in democracy and foster connections with each other: a national service program, civic education, and deliberative democracy. I also include the role of transformative leadership because I think America still very much has a hero culture. We need the citizen exemplar that embodies the next version of who we want ourselves to be and what we want the nation to be. These recommendations are all ways to manufacture connections that don't naturally exist in a nation as large, diverse, and spread out as ours is.

DS: Say more about what you call national solidarity and why it is so important to foster.

TJ: What I'm calling national solidarity is basically a combination of political and civic solidarity. It is about the duties that people have to one another to ensure the equality that everyone has a right to, like equal protection under the law and the full rights and privileges of citizenship. It is the duty that we have to one another to ensure all of us can touch the fruits of constitutional democracy. It's about the social contract, the duties that people have to the state and that the state has to the people. What I am calling national solidarity is when people bond together to hold the state accountable, because the state has infringed upon the rights of citizenship of some of the public. All the people are coming together because some of them are not realizing the fruits of the democracy like others are, and they're holding the state accountable. This plays off seeing racism as a crime of the state. National solidarity is an effective bond of kinship between citizens to hold the state accountable and make it do what it's supposed to do, which is ensure that we all have equality, liberty, opportunity, security, etc.

DS: You talk about the "superlative citizenship" demonstrated by Black Americans in our history as an embodiment of the kind of national solidarity that all of us need to be displaying at this juncture. What are the hallmarks of this form of citizenship?

TJ: The book sketches out what national solidarity could look like by looking at the group solidarity within Black America that has persisted since Africans' arrival. Superlative citizenship is living up to your end of the social contract, even when the state is in breach of its end. This is Black Americans fighting in the Revolutionary War, in the War of 1812, and in the Civil War, despite being enslaved. This is Black Americans fighting in World War I and II, then returning home only to be lynched, to have no access to jobs and economic security and physical safety. And yet they have continued to serve in every conflict the nation has ever had, knowing that they did not taste the very democracy that they were going off to die for, or at least willing to risk their lives for.

Another version of this is respectability politics. It has been falling out of favor recently, but a century ago, it was a survival mechanism blacks used to counter the white narrative that they were deficient in some way in their intelligence, morals, or culture, by living up to all of the American norms, social diction, and dressing up to perform the role so that if whites denied them citizenship, it's not because there was something faulty with the people who sought it.

We saw glimpses of this type of superlative citizenship last summer, with Black Lives Matter protests happening in every state in the country, black and white people together, even in places where there were no black people around, like in Idaho! That was significant. It actually showed me that my argument wasn't too Pollyanna. There was real evidence that we could pull off the kind of national solidarity I'm arguing for, and trying to lay out a path for how to get from here to there. But it also showed me that even though we could touch it as we did, that is different from it being able to endure. Last summer gives evidence that it is possible to achieve national solidarity. The question is, can we make it deeper, thicker, more resilient? Can we begin to fashion it in a way that it comes indoors and can be operationalized so that we could begin changing our government and our socio-economic structures? That's the part that now feels like the long pole in the tent instead of, is the thing even real? Can we even touch it?

DS: Last question: this is a book that blends political science, history, and sociology with the lived experience of racism that generations of your family and you have had to endure, being citizens and in your case serving in the military of a country that continues to fall short of its ideals. It makes such a powerful argument because it is a highly personal one. How are you feeling now that you are about to launch this book?

TJ: It has been tough, bringing all those things together. As you say, it is one-third memoir, one-third historical analysis, and one-third social science and theory. I try to mash all these things together to tell a story that at once is well researched and rigorous and intensely personal. If this was all theory or all political analysis, I don't know that I would have anything particularly new to say that others haven't said, but the family and personal story makes it tangible in a way that feels novel. I could show all the data in the world, I could cite all the great scholars, and people are unlikely to be moved. But when they read about my three-times great-grandfather on my mother's side who was an African slave in Florida who only wanted freedom; and on my father's side being the product of enslaved people and Scots-Irish free people, knowing that the child could only touch as much freedom as the mother could, and not as much as the father could; and yet both sides of the family find some way to not lose hope in the country, find some way to navigate the terror and the racism, it makes me feel like their hope in America isn't misplaced.

I tell the story about my name being Theodore Roosevelt Johnson III because of the dinner that Teddy Roosevelt had with Booker T. Washington at the White House in 1901. My great-grandparents, like many other black folks in the South, were really moved by that. So, I end up being named after the rich white New Yorker and not after the black educator who was so revered by blacks at that time, almost as a protest against the station to which my ancestors had been relegated based on the racial politics of the day. The family stories march through the history and the political analysis to show that it's not just theory, it's not just characters in a history book, but that these things have real implications for everyday people. And my hope is that no matter your race, you will see America in my family's story.