Reimagining the Light but Sturdy Ballast of the Pork Barrel

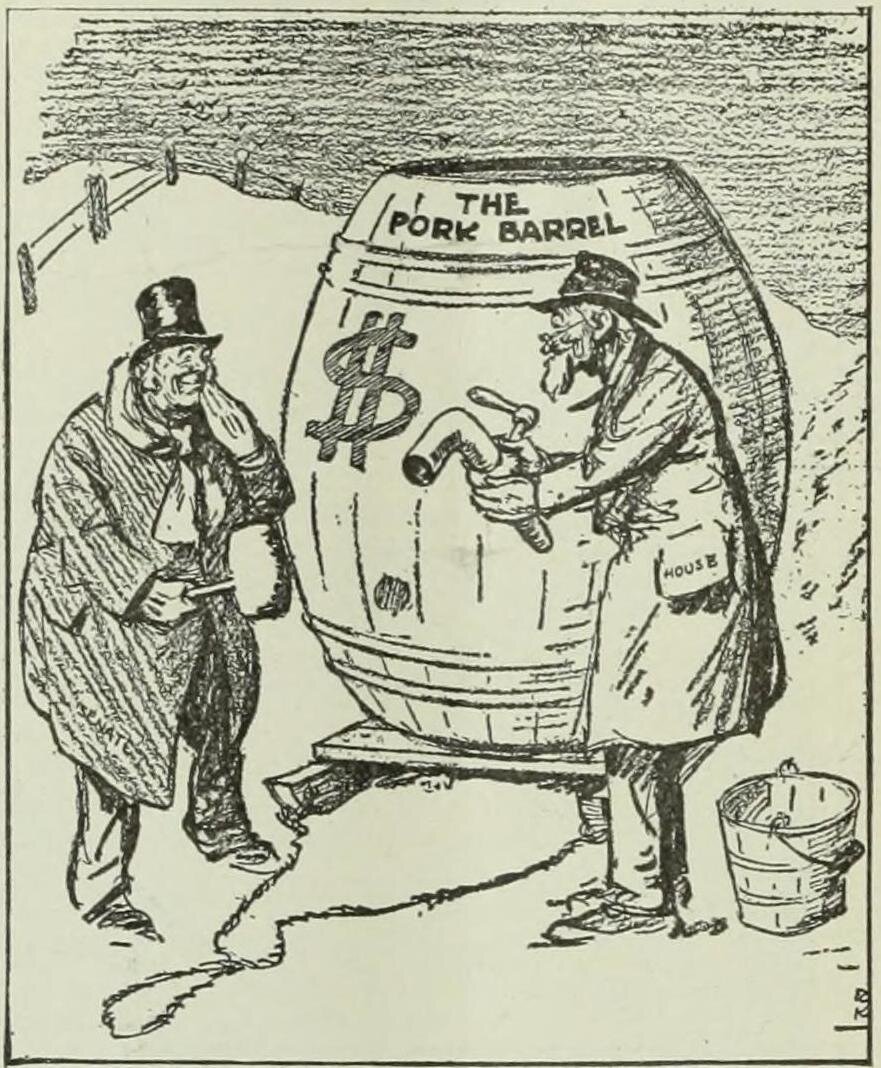

Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

We have endured an unceasing crescendo of high politics over the past four months. We staggered from a contested election, to an insurrection inspired if not incited by the outgoing president, to a locked-down inauguration of his successor, to an impeachment trial. In the spirit of offering a respite from the sturm und drang, let's consider a promising albeit prosaic reform idea percolating on Capitol Hill: re-establishing congressional earmarks. The republic's fate will not hinge on this change alone, but it could, in incremental ways, improve our government, politics, and civil society.

Members of Congress earmark legislation when they insert language into it or supporting documents that directs federal spending to specific projects, e.g., highways, bridges, power grids, defense contracts, community centers, cultural sites, research laboratories, etc. Almost invariably, these projects reside in the state or district of the legislators doing the earmarking. The legislators, in turn, claim credit and accrue political benefits for their earmarks back home.

In aggregate, earmarks give rise to pork-barrel politics, a metaphor meant to conjure up many people taking just a little bit of a large collective resource to use for their own purposes. The pattern prompts questions and criticism about whether this is the best use of taxpayer dollars. For many years, legislators adept at earmarking could rebuff these charges with a wink and a nod. Trent Lott became legendary (and won a dozen congressional elections) by bringing home prodigious amounts of bacon for the shipyards and levees of his native Mississippi. Lott was fond of saying that, as far as he and his constituents were concerned, pork was simply another name for federal spending north of Memphis.

However, over the past three decades, a bipartisan reform coalition has put earmarkers on their heels. It picked up steam in the early 1990s when Republican backbenchers like John Boehner refused to seek earmarks for their constituencies as a point of small government principle. At the same time, good government watchdogs across the political spectrum like Citizens Against Government Waste and Taxpayers for Common Sense began throwing a harsh spotlight on how some of the earmarks served the special interests of politicians, donors, and lobbyists at the expense of the public interest.

By the mid-2000s, as earmarked spending approached a highwater mark of $30 billion annually – roughly 1% of the federal budget – the critics gained the upper hand. The outcry when Alaska Representative Don Young and Senator Ted Stevens earmarked $223 million for the infamous Gravina Island Bridge, aka the Bridge to Nowhere, helped break the camel's back. So did the discovery that California Representative Randall "Duke" Cunningham had accepted $2.4 million in bribes from defense contractors in exchange for earmarked spending. John McCain made a pledge to veto earmarked bills a central feature of his 2008 campaign, and Barack Obama also committed to combatting them.

As president, a consternated Obama discovered he had little choice but to sign earmarked bills in the early years of his administration—and drew criticism as a hypocrite for doing so. Duly stung, he vowed in his 2011 State of the Union address he would veto any future bills Congress sent to him containing earmarks. By then, however, the new GOP Majority in the House, led by Speaker John Boehner, and pushed by the Tea Partiers now in their midst, had already banned earmarks via a party caucus rule. Given the Republicans' control of the House, their vows of abstinence effectively tied the hands of legislators in both parties.

How has the earmark ban worked out? Paradoxically, good government reforms often generate unanticipated and adverse consequences that leave the polity worse off. For example, throughout the 20th Century, democracy reformers advocated for primary elections to select party nominees because they wanted to take this power from political bosses in smoke-filled backrooms and give it to voters. Alas, the primary elections that have now become universal empowered an even more pernicious set of elites: the highly ideological and hyper-partisan activists and voters, representing a narrow slice of the electorate, that drive our polarized politics.

We can recognize a similar pattern with the earmark ban. Federal officials still designate funds for specific projects. But now executive branch administrators are the ones making the decisions. They lack legislators' local knowledge and accountability, but they have a clear interest in enhancing the political fortunes of the president and his party. Thus, the earmark ban has contributed to the ongoing shift in power from Congress to the presidency that threatens to subvert the Constitution's checks and balances, including the power of the purse that Article I gives to the legislature.

The earmark ban has further contributed to this shift by making it harder for Congress to pass appropriations bills. Members no longer have the incentive to vote for a tough bill that nonetheless includes something concrete they can bring home to their constituents. In the ten years since the earmark ban went into effect, Congress has passed only 6 out of the 120 appropriations bills it was meant to by the start of the next fiscal year. Congress cannot wield the powers of the purse the Constitution gives to it if it cannot marshal majorities to pass appropriations bills in a timely way.

Banning earmarks has also worked to loosen the ties binding legislators to the states and districts they represent. It has thereby helped accelerate the nationalization and polarization of politics threatening to pull the country apart. More and more, we see members of Congress – and they see themselves – as politicians beholden to a party and its leadership, not to a particular place and the diverse range of people, perspectives, and interests within it. Witness the furious censures that state and local Republican Party organizations have levied against federal lawmakers for voting against President Trump during the impeachment proceedings. Witness also Senator Ted Cruz decamping from Houston to Cancun with his family just as a massive emergency struck Texas. An unstinting partisan, Cruz didn't see it as part of his job description to represent his beleaguered constituents and help them cut red tape in their hour of need as only a U.S. senator can. This party-over-constituency perspective is not exclusively a Republican blindspot. Consider the mounting frustration expressed by progressive Democrats toward moderates like West Virginia's Joe Manchin and Arizona's Kyrsten Sinema, or Michigan's Elissa Slotkin and Virginia's Abigail Spanberger, as they seek to represent constituencies that are purple or, in Manchin's case, deep red.

Fortunately, a group of institutionally-minded legislators in Congress have recognized the need and opportunity to revisit the earmark ban. Their work began in earnest with the best-kept secret in Washington: the House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress. Established with overwhelming bipartisan support in early 2019, the Select Committee has been working behind the scenes to identify and propose reforms that would strengthen the House, and by extension Congress, as an institution. Consisting of an equal number of Democrats and Republicans, the Select Committee has to date vetted and approved 97 proposals, many of which the House has already adopted. These include provisions for how the House orients and supports new members, hires and trains staff, uses and secures technology, and makes data and information about its work available to the public. Recommendation #85 on the Select Committee's list of proposals, in a subset designed to help "Reclaim Congress's Article I Powers," is its call to,

"Reduce dysfunction in the annual budgeting process through the establishment of a congressionally-directed program that calls for transparency and accountability, and that supports meaningful and transformative investments in local communities across the United States. The program will harness the authority of Congress under Article I of the Constitution to appropriate federal dollars."

The Select Committee has in effect been serving as a test kitchen for the House, developing bipartisan solutions to thorny institutional questions that would be impossible for one party or the other to advance on its own in the current polarized environment. By re-envisioning earmarks as a "community-focused grant program," the Committee has done so very ably in this instance as well.

Indeed, last Friday, February 26, House Appropriations Chair Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut shared her Committee's plans for enabling legislators to request earmarks for "community project funding" in appropriations bills along the lines that the Select Committee mapped out in its proposal. As DeLauro stated in her announcement:

"‘Community Project Funding will allow Members to put their deep, first-hand understanding of the needs of their communities to work to help the people we represent….Community Project Funding is a critical reform that will make Congress more responsive to the people….’ In addition, Chair DeLauro noted that Community Project Funding will help Congress regain control of federal spending from the Executive Branch. ‘Community Project Funding restores balance on important decisions about how and where to spend taxpayer dollars, allowing Members of Congress to bring their knowledge and experience to the decision-making.’"

The Appropriations Committee's reform plans include measures the Select Committee proposed to prevent the abuses of the past, including end-to-end, online transparency for all requests, expanded bans on self-dealing, no funding of for-profit entities, independent audits, and an overall spending limit pegged at one-percent of discretionary spending. The most intriguing but least fleshed-out aspect of the Appropriations Committee's plan is its requirements for "Demonstrations of Community Engagement." It notes that members requesting earmarks "must provide evidence of community support that were compelling factors in their decision to select the requested projects" and goes on to note that "this policy was recommended by the bipartisan House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress."

Given this is all that DeLauro's announcement says about this aspect of the new approach to earmarks, let's delve into the Select Committee's recommendations for community engagement:

"Unlike prior endeavors that put the nomination and decision-making process in the sole hands of Members, this program will start outside of Washington and in the communities Members represent. Grant requests must originate with a public entity (including not-for-profit entities that serve a public interest) or state, local, or tribal governments (including subdivisions of state or local governments and including a local community or public entity collaborating with a Member of Congress to identify a local priority) via formal application submitted to at least one congressional office. Recognizing issues related to community capacity, the Committee also acknowledges that this may also include a local community collaborating with a Member of Congress to identify a local priority.

The Committee felt it was important to allow not-for-profit entities to apply for a Community-Focused grant, given the valuable services many provide to communities across the nation. From schools and hospitals, to conservation programs and historical preservation efforts, the range of services provided by not-for-profit entities vary greatly across the country. One of the top priorities of the [Community Focused Grant Program] was to allow communities and Members to have the freedom to identify projects in most need of funding. Ruling out not-for-profits could hamstring that goal.

The Committee took important steps to ensure the process was easy for all communities across the nation to navigate—whether a large city with grant coordinators on staff or smaller, rural towns without resources on hand to help them navigate the grant process."

The Select Committee is thus reimagining earmarks as a means for connecting federal lawmakers with the communities they represent. The goal is an interactive, two-way partnership between members of Congress, on the one hand, and the state and local government agencies, nonprofit groups, and civic leaders whose work provides essential scaffolding for civil society, on the other. It remains to be seen whether and how the Appropriations Committee will follow through on the Select Committee's recommendations for community initiative and engagement as it goes about re-establishing earmarks. Doing so would certainly help defuse the criticism that is already coming from opponents of the practice within and outside of Congress. Those of us who would like to see a stronger Congress, a politics that better reflects the diversity of people, perspectives, and places in the country, and a more vibrant civil society have an interest in seeing this thoughtful reimagining of earmarks succeed.